The Indian state is obsessively constructing new dams in the Himalayas particularly in the occupied territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The constructions serve many purposes for the usurper, but top of the list is weaponizing water against its nuclear neighbor Pakistan while at the same time bringing to ruins an entire civilization that is the occupied population of Kashmir.

It is pertinent to note here that the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganization Act passed in 2019 gave the Indian administration a direct physical and “legal” control over the water that flows through the occupied territory, including the partitioned rivers that are already a major bone of contention between India and Pakistan. The dams are undeniably a part of ‘strategic investments’ to maintain India’s critical control over disputed waters.

The popular narrative being promoted is that India is assimilating the Kashmiri population with the mainland work culture of India through the dam projects and letting them have a share in the modern capitalist framework. According to Mona Bhan, this idea roots in viewing Kashmiris as lazy and indolent, a ‘cultural idiom’ working as a political label to legitimize the state’s iron control over the region. It attempts at mainstreaming the Kashmiri youth to participate in the flourishing of Indian economy, as they are being forcibly inducted into new forms of wage and corporate labor since the construction of dams began. (1)

INDIA’S HYDROELECTRIC PROJECTS UTILIZING KASHMIRI WATERS

The Diplomat reports construction of seven new dams in Kishtwar, a region of dense forest in Indian Illegally Occupied Kashmir, with estimated generation of 5,190 megawatts of hydroelectricity – Bursar Dam (800 MW), Pakal Dul (1000 MW), Kwar Dam (540 MW), Kiru Dam (624 MW), Kirthai-I (390 MW), Kirthai II (930 MW), and Ratle Hydroelectric project (930 MW). Work on four of the dams has already begun. Over 70 major hydroelectric projects on the Chenab are in various stages of planning, construction, and operation with a combined capacity of over 13,000 MW. (2)

The building of dams and associated hydropower projects begs a loud question: “Does India actually have the right to utilize the waters however it aims to?”

LEGAL PERSPECTIVE

A recent survey by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) analyzing data collected by satellites between 2003 and 2013, indicates that Indus Basin is the second most overstressed water basin in the world, with its water levels falling by four to six mm every year which leads us to understand the importance of Indus water Treaty. (3)

The Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, signed between India’s first prime-minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Pakistan’s then president, Gen. Ayub Khan, dividing six rivers among India and Pakistan, delineates that India can use the rivers allocated to Pakistan only for domestic, non-consumptive, agriculture and hydro-power generation purposes. Also, it is not allowed to exercise its rights over transboundary rivers to the detriment of its neighbor, a legal clause repeatedly disregarded by the Government of India.

Violations of the Treaty by the Government of India

While India controls exclusive water use for three of the six rivers, it physically lies upstream to all six rivers. Crucially, Jammu & Kashmir physically lie upstream of two out of three of Pakistan-controlled rivers. If India were to divert all the upstream river waters within its borders, in violation of the Indus Water Treaty, India could cripple Pakistan’s resources.

MAJOR PROJECTS – MAJOR CONTROVERSIES

The Baglihar Power Project

The Baglihar Dam or 430 MW Baglihar Project, initiated in 1999 and completed in 2008, built on the Chenab River in the southern Doda district of the Indian Occupied Jammu and Kashmir is designed for the non-consumptive use of the river water. It is a run-of-the-river hydroelectricity project and under the guise of storage in the dam to gain steady tide for production, India has built the dam about 4.5 m above the highest water level. (4) Using this level to its advantage, India reduced the flow of water in Chenab River during the sowing period of August to October 2008. The result was enormous agricultural damage for Pakistan owing to a loss of nearly 23000 cusecs of water. Along with this, the outlets of the dam are built too low in the walls of the dam supposedly for clearing of silt but multi-purposely flooding the areas downstream, particularly in the destructive floods of 2010.

The Kishanganga Project

The Kishanganga is a Sanskrit name derived from the Hindu scriptures alluding to the religious origins of the water war. It appears that India is religiously motivated to harness its electricity by gaining control over the Kashmiri waters.

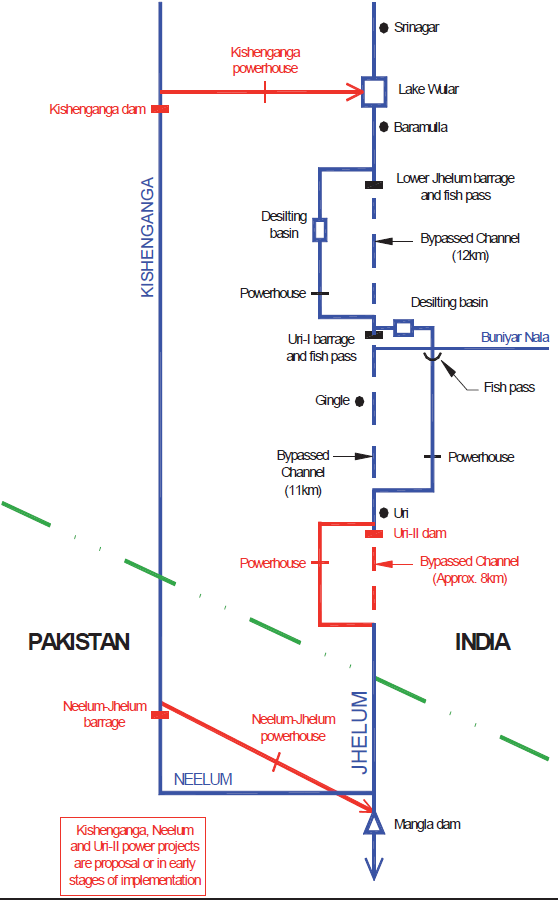

The Kishanganga project is built on the Kishanganga River or the Neelam River, a tributary of the Jhelum, makes non-consumptive use of water and releases its discharge through a 22-km tunnel into the Wullar Lake on the Jhelum. Pakistan has also initiated its mega Neelum-Jhelum Link Hydroelectric Project (NJHP) on river Neelam. India’s cunning design reduce the flow of water by 27% and the power potential of NJHP by 9.25%. (5)

It is pertinent to mention that in the 2013 case between India and Pakistan, the arbitration tribunal concluded that while India was entitled to construct the disputed power-generation project on the Kishanganga/ Neelum River, its right to use the shared waters was limited by the constraints specified by the Indus Waters Treaty and customary international law endorsed by the International Court of Justice (ICJ). The law clearly mentions that a country cannot unilaterally assume control of shared resources and deprive another riparian country of its right to an equitable and reasonable share of the natural resources of rivers. (3)

The Bursar Dam

Another gross violation of the treaty is the Bursar Dam constructed on Marusudar River in Doda District as its storage was much behind the permissible limits along with being in Seismic Zone V and hence most vulnerable to earthquake.

A LOOK AT THE HARMS DONE TO THE VALLEY BY THE NEW CONSTRUCTION PLANS

The construction of large dams has repercussions for the whole ecosystem, including the indigenous people whose livelihoods depend on rivers and the agricultural lands. According to the World Commission on Dams (WCD), the end of any dam project must result in sustainable improvement of human welfare, that is, it must be economically viable, socially equitable and environmentally sustainable. This is another example of principles that India has turned a blind eye to, on numerous occasions with impunity.

Mass displacement with no Compensations

The projects are causing displacement of indigenous communities much to everyone’s expectations, however what is way out of the line, but again appropriate to the colonizer’s rule book, is how poorly and negligibly these locals are being compensated. The self-efficacious villagers on average possessing 6 canals of agricultural land in the uprooted areas were given one third of the allotment price and forced to move in to nearby villages where they had no aid from the government whatsoever in finding means of sustenance from scratch.

The Hindustan Construction Company that earned the Kishanganga Project contract refuses to take upon itself the responsibility of providing jobs and rehabilitation to the Gurezis shunting the onus to the NHPC. (1) The NHPC shifts the task to the district government and its deep woven networks of bureaucracy. The two corporate giants along with bureaucracy are hence collectively to be credited for a deliberate failure to address the miseries of displaced and unemployed community which is subjected to humiliation for their justified demand for compensation and rehabilitation rights. Needless to say, the authorities are unaccountable and a cut above the law.

The natives of villages including Sirchi, Pohar, Krosa Sounder, and Sewarbatti Dachan who depended on the forest for survival now living hand to mouth protested against the tyrannical invasion and insufficient recompense but were met with threats from the NHPC to have Public Safety Act thrust upon them. In the name of a legal procedure, their case files are being shunted office to office with futile promises. (2)

Ecological Alarms and Earthquakes

Along with wrecking the local lives and provisions, the relentless building activities in the well-known seismic areas like the Chenab Valley is raising ecological alarms with risks of destructive earthquakes. Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., observes, “There’s reason to worry about the ecological balance, impacts on marine life in the Chenab River, and earthquake risks. This is an area of high seismicity, and that means large-scale dam development could increase the chances of a major earthquake.” (2)

The Sawalkot project is located in Doda and Udhampur districts of occupied Kashmir. It has a capacity of 1,200 MW and is highly vulnerable to earthquake, being in the seismic zone of Kashmir Himalayas, and poses danger not only to occupied J&K but also to Pakistan.

Loss of Habitat and Seasonal Crops

Resettlement, downstream hydrology, muck generation and disposal, loss of forest land and habitats, and impact on fish such as the famous Chenab Trout are a few of the issues arising out of these hydropower projects. The disruption of climate resulting from these construction cascades affects other neighborhoods, causing persistent rain followed by intense heatwave, hence leaving virtually no ground or ambiance for growth of crops.

Submerged Villages

Submergence is another looming danger for the surrounding villages. The raised water level makes them prone to complete drowning making it seem fit for the Indian state’s designs, wielding hydropower at the cost of subdued Kashmiris. The 800-MW hydroelectricity project on Marusudar – will submerge nearly a dozen villages and displace hundreds of families. Marusudar is also the largest tributary of the Chenab – a river that flows into Pakistan.

In Gurez, the Kishanganga Dam has completely submerged the villages of Khopri and Badwan, also drowning down the last refuge of Dard-Shin tribal people who are the original inhabitants of Kashmir. The replacement of ancestral homelands for the local population amounts to a complete uprooting of identity through uprooting of birthplaces. (1)

Poverty Rife and Unemployment galore

A fuel for India’s economy, celebrated by the corporate sectors, is also a poorly disguised means to suppress the insurgency movements in Kashmir, perpetrating the reign of terror and bringing about mass unemployment and poverty in the local Kashmiri population.

The demand for entitlements and compensation is pictured as greed by the occupier and the local disputes among the displaced people over land and resources is being played upon by the authorities to further reinforce their ‘humanistic tropes’ framing them as indolent and accustomed to a lazy life.

These actions also project Kashmir as a resource-poor land dependent on the mainland India to fill its ‘begging bowl’- a terribly undignified label that shadows India’s reliance on the region’s plentiful water power as a tool to support its own vulnerable economy. Kashmiris vehemently reject these labels as they are in fact well suited to the NHPC’s exploitation of their rivers in context of the Indus Water Treaty and attribute these projects to be a part of India’s ‘hydraulic colonialism’ and an assault on the land’s sovereignty. (1)

CROSS-BORDER PROPAGANDA

On the other hand, the construction of dams in Pakistan is also being maligned by the Indian propagandists as discrimination and injustice to the people of Azad Jammu and Kashmir. This accusation is baseless and easily falsified.

As per Hydropower Royalties: A Comparative Analysis of Major Producing Countries by Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI) published in April 2017, Pakistan pays one of the highest per kWh (unit) rates in the world in terms of the Net Hydel Profits (NHP) or royalty to the provinces and federal territories which amounts to Rs1.10 per kWh as Net Hydel Profit (NHP) in contrast to Rs 0.48 paid by India. The Combined Annual NHP (royalty) of Mangla Dam and NJHPP is Rs 17,046,084,000 (Rs 17.046 billion) and if we look into the budget 2020-21 of AJK, we shall see, more or less, same amount (Rs 16.9 billion) which the Government of AJ&K has included in the budget receipts. (6)

References

1. Bhan, Mona. MORALITY AND MARTYRDOM: DAMS, “DHARMA”, AND THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF WORK IN INDIAN-OCCUPIED KASHMIR. Biography. December 2014, pp. 197-217.

2. Nabi, Safina. India’s Grand Plan for Kashmir Dams. The Diplomat. 2022.

3. Kaszubska, Preety Bhogal and Katarzyna. The Case Against Weaponising Water. ORF Issue Brief. 2017, 172.

4. Bansal, Alok. Baglihar and Kishanganga: Problems of Trust. 2005.

5. Jamal, Haseeb. Impact of Indian Dams in Kashmir on Pakistani Rivers. 2017.

6. Khan, Sardar Abdullah. Hydroelectricity Production in AJ&K and Myths Attributed to its Royalty. The Kashmir Discourse. 2020.